Minimal Schedule with Minimal Number of Agents in Attack-Defence Trees

This repository hosts the results for the paper and for its journal version.

Clone this repository:

git clone --recurse-submodules https://depot.lipn.univ-paris13.fr/parties/publications/minimal-scheduling.git && cd minimal-schedulingFolder Structure

.

├── benchmarks # folder with the scripts to generate the benchmarks for adt2amas and adt2maude

├── results # folder with the ADTree models and the minimal assignments

├── scalability # folder with the scripts to generate the scalability results

└── tool # folder with the binaries of the tool adt2amasResults

The minimal scheduling results can be found in the results folder. The reader

can found the sources of the adt2amas tool

here,

and the sources of the adt2maude

here. Binaries for

multiple OS of the adt2amas tool can be found in the folder tool. The script

tool/adt2maude/install-deps.sh downloads the dependencies of the adt2maude

tool.

In order to reproduce the results, the command to be executed is the following:

# Change adt2amas-linux command by the binary corresponding to your OS.

./tool/adt2amas-linux minimal --print-latex --print-scheduling --model results/<case_study>/model/<case_study>.txtor

# adt2maude

./tool/adt2maude/min-schedule.py --table --input results/<case_study>/model/<case_study>.txtBelow we show some case studies.

- Forestalling a software release (forestall)

- Obtain admin privileges (gain-admin)

- Interrupted

- Compromise IoT device (iot-dev)

- Last

- Lukasz

- Lukasz-or

- Example from [5]

- Treasure Hunters

- Scaling Example

Forestalling a software release (forestall)

This model is based on a real-world instance [1]. It models an attack to the intellectual property of a company C, by an unlawful competitor company U aiming at being “first to the market.” Following [2], software extraction from C takes place before U builds it into its own product, and U must deploy to market before C, which takes place after U has integrated the stolen software into its product.

ADTree model

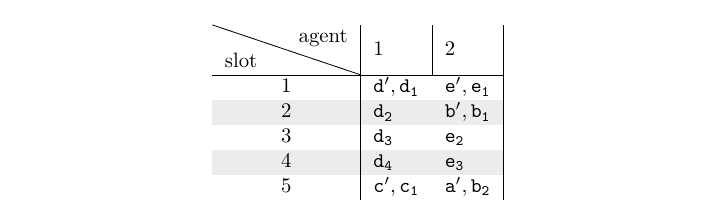

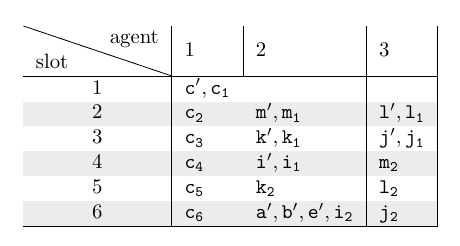

Minimal Scheduling

The reader can find the 4 possible assignments here.

Obtain admin privileges (gain-admin)

To gain administrative privileges in a UNIX system, an attacker needs either physical access to an already logged-in console or remote access via privilege escalation (attacking SysAdmin). This case study [3] exhibits a mostly branching structure: all gates but one are disjunctions in the original tree of [3]. We enrich this scenario with the SAND gates of [2], and further add reactive defences.

ADTree model

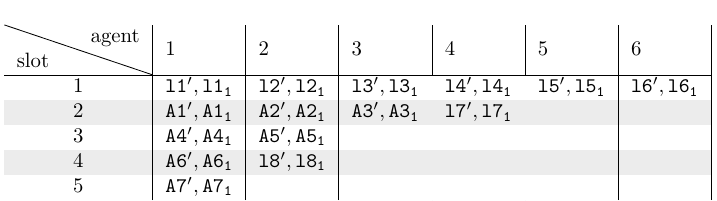

Minimal Scheduling

The reader can find the 16 possible assignments here.

Interrupted

ADTree model

Minimal Scheduling

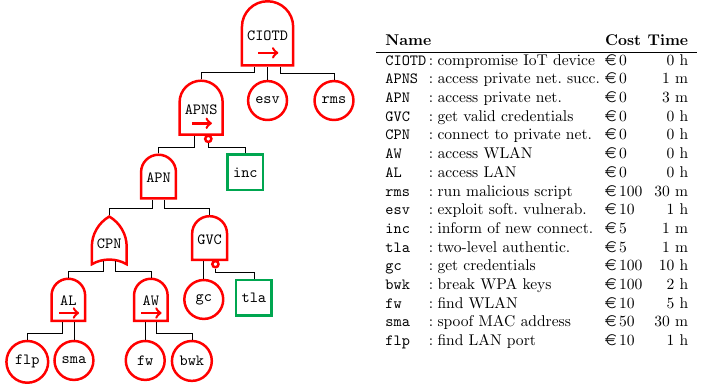

Compromise IoT device (iot-dev)

This model describes an attack to an Internet-of-Things (IoT) device either via wireless or wired LAN. Once the attacker gains access to the private network and has acquired the corresponding credentials, it can exploit a software vulnerability in the IoT device to run a malicious script. Our ADTree adds defence nodes on top of the attack trees used in [4].

ADTree model

Minimal Scheduling

The reader can find the possible assignment here.

Last

ADTree model

Minimal Scheduling

Lukasz

ADTree model

Minimal Scheduling

The reader can find the possible assignment here.

Lukasz-or

ADTree model

Minimal Scheduling

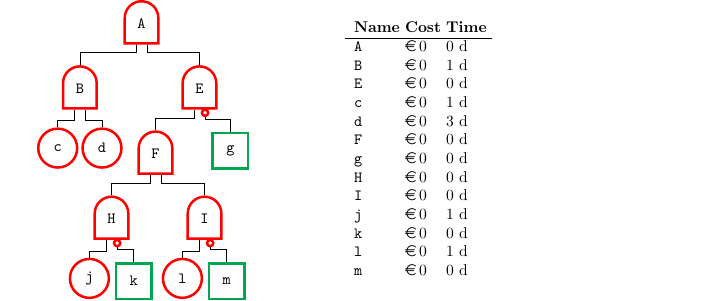

Example from [5]

ADTree model

Minimal Scheduling

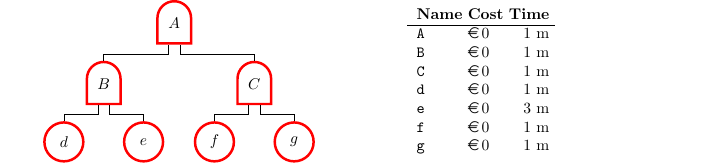

Treasure Hunters

It models thieves that try to steal a treasure in a museum. To achieve their goal, they first must access the treasure room, which involves bribing a guard (b), and forcing the secure door (f). Both actions are costly and take some time. Two coalitions are possible: either a single thief has to carry out both actions, or a second thief could be hired to parallelise b and f. After these actions succeed the attacker/s can steal the treasure (ST), which takes a little time for opening its display stand and putting it in a bag. If the two-thieves coalition is used, we encode in ST an extra 90 € to hire the second thief — the computation function of the gate can handle this plurality — else ST incurs no extra cost. Then the thieves are ready to flee (TF), choosing an escape route to get away (GA): this can be a spectacular escape in a helicopter (h), or a mundane one via the emergency exit (e). The helicopter is expensive but fast while the emergency exit is slower but at no cost. Furthermore, the time to perform a successful escape could depend on the number of agents involved in the robbery. Again, this can be encoded via computation functions in gate GA.

As soon as the treasure room is penetrated (i.e. after b and f but before ST) an alarm goes off at the police station, so while the thieves flee the police hurries to intervene (p). The treasure is then successfully stolen iff the thieves have fled and the police failed to arrive or does so too late. This last possibility is captured by the condition associated with the treasure stolen gate (TS), which states that the arrival time of the police must be greater than the time for the thieves to steal the treasure and go away.

ADTree model

Minimal Scheduling

The reader can find the possible assignment here.

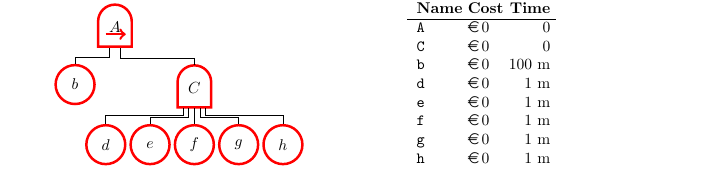

Scaling Example

ADTree model

Minimal Scheduling

Scalability Results

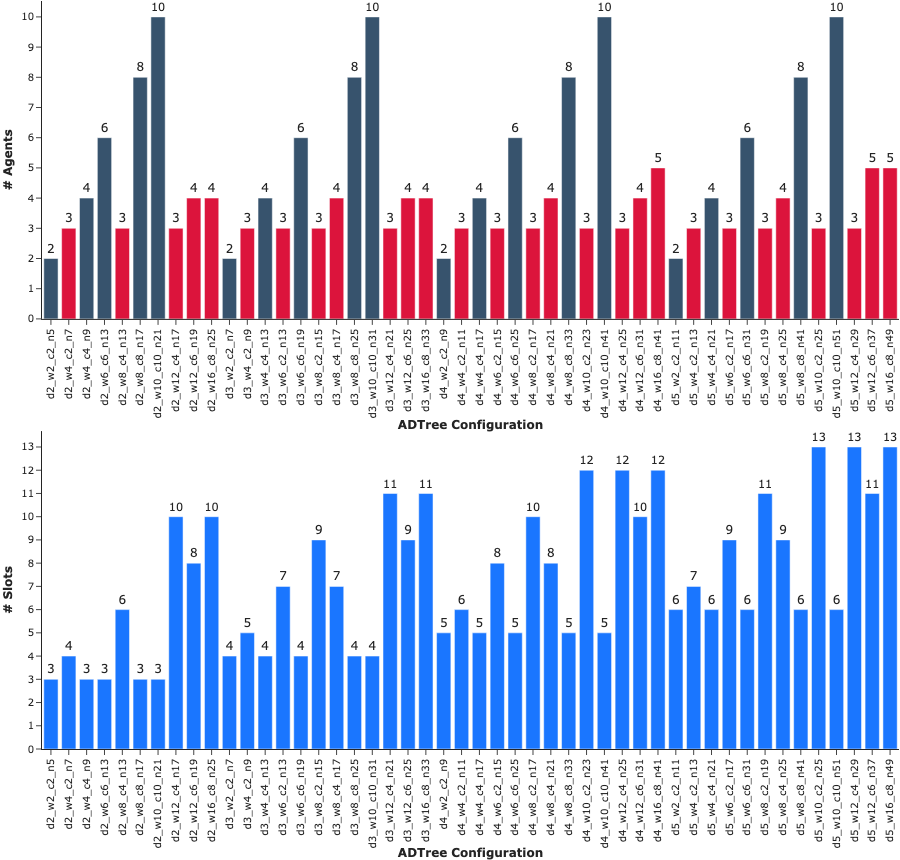

We wrote an automatic generator of ADTrees and a notebook that processes the

output of our tool in order to create the figure shown in the paper. The scripts

are detailed in the scalability folder.

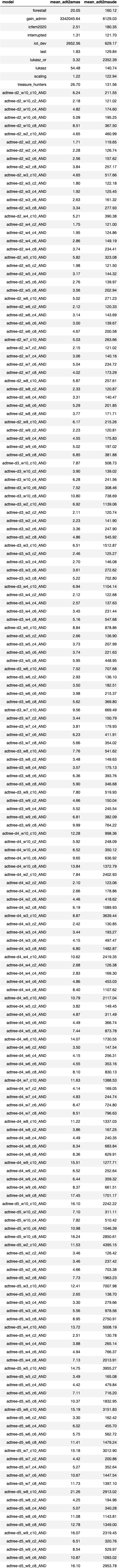

The parameters of the generated ADTrees are the depth, the width corresponding to the number of deepmost leaves, the number of children for each AND, and the total number of nodes. All nodes have time 1 except the first leaf that has time width - 1. The results show that the number of agents is not proportional to the width of the tree (red bars - top of Figure), and the optimal scheduling varies according to the time of nodes (blue bars - bottom of Figure).

Benchmarks

We wrote a script to run the benchmarks and a notebook that processes the output

of the script in order to create the table shown in the paper. The scripts are

detailed in the benchmarks folder. The times shown in the table are in

milliseconds.

Authors

- Jaime Arias (LIPN, CNRS UMR 7030, Université Sorbonne Paris Nord)

- Łukasz Maśko (Institute of Computer Science, PAS, Warsaw University of Technology)

- Carlos Olarte (LIPN, CNRS UMR 7030, Université Sorbonne Paris Nord)

- Wojciech Penczek (Institute of Computer Science, PAS, Warsaw University of Technology)

- Laure Petrucci (LIPN, CNRS UMR 7030, Université Sorbonne Paris Nord)

- Teofil Sidoruk (Institute of Computer Science, PAS, Warsaw University of Technology)

Abstract

Expressing attack-defence trees in a multi-agent setting allows for studying a new aspect of security scenarios, namely how the number of agents and their task assignment impact the performance, e.g. attack time, of strategies executed by opposing coalitions. Optimal scheduling of agents' actions, a non-trivial problem, is thus vital. We discuss associated caveats and propose an algorithm that synthesises such an assignment, targeting minimal attack time and using the minimal number of agents for a given attack-defence tree. We also investigate an alternative approach for the same problem using Rewriting Logic, starting with a simple and elegant declarative model, whose correctness (in terms of schedule's optimality) is self-evident. We then refine this specification, inspired by the design of our specialised algorithm, to obtain an efficient system that can be used as a playground to explore various aspects of attack-defence trees. We compare the two approaches on different benchmarks.

References

[1] A. Buldas, P. Laud, J. Priisalu, M. Saarepera, and J. Willemson. Rational Choice of Security Measures Via Multi-parameter Attack Trees. In Critical Information Infrastructures Security, pages 235–248. Springer, 2006.

[2] R. Kumar, E. Ruijters, and M. Stoelinga. Quantitative attack tree analysis via priced timed automata. In FORMATS 2015, volume 9268 of LNCS, pages 156– 171. Springer, 2015.

[3] J. D. Weiss. A system security engineering process. In Proceedings of the 14th National Computer Security Conference, pages 572–581, 1991.

[4] R. Kumar, S. Schivo, E. Ruijters, B. M. Yildiz, D. Huistra, J. Brandt, A. Rensink, and M. Stoelinga. Effective analysis of attack trees: A model-driven approach. In Fundamental Approaches to Software Engineering, pages 56–73. Springer, 2018.

[5] J. Arias, C. E. Budde, W. Penczek, L. Petrucci, T. Sidoruk, and M. Stoelinga. Hackers vs. Security: Attack-Defence Trees as Asynchronous Multi-agent Systems. In Formal Methods and Software Engineering, vol. 12531, pages 3-19. Springer, 2020.